Stamped Brasses

By Maurice A. Hill.

There are various names that can be used to describe this type of harness decoration: stamped brasses, pressed brasses, metals, medallions, plates, the list goes on and on. The correct name for them would be pressed brass harness decorations, however this is a bit of a mouthful.

Whatever you might like to call them it may surprise collectors to learn that there is very little specialist reference material about them as no serious attempt to fully record them had, until recently, been undertaken. Various authors like H.S. Richards in 1944 included a few examples in his three volume work and fortunately many more later appeared in the publications by the National Horse Brass Society. It was not until I decided to attempt my private publication, Stampers, did I fully appreciate the enormous task it was to be and why it had not been undertaken before. Sourcing the variations was exceptionally difficult.

Stamped brasses appeared on the scene around 1880, with a small number occurring perhaps a decade or so earlier. However, production of these appears to have peaked shortly before the First World War. Since the 1920’s, a few types have been produced but their quality is rather poor being made from thinner gauge brass sheet.

Due to serious considerations of the sheer weight of cast harness decorations carried by working horses (first raised by the early animal welfare movements in the late 19th C.) it is thought that the first stamped brasses were made as a lighter, (and cheaper) alternative to cast brasses being later exported throughout the British Empire. Unlike their cast cousins, stamped brasses were not made in moulds, but pressed out of rolled sheet brass approximately 1/16 in thickness although other gauges of sheet than earlier examples.

Below; pages 44 & 45 of Hampson and Scott's Equine Album of C.1890's showing a page of stamped brasses & Rosettes.

Production and the finished product

The machine used to do this was called a Flypress (often called a flywheel press). These machines were mechanically driven rams; meaning the power to the ram is provided by a heavy, constantly rotating flywheel. The flywheel drove the ram using a Pitman arm. In the 19th century, the flywheels were powered by leather drive belts attached to line shafting, which in turn ran to a steam plant.

These early pre ssing machines stamped out blanks complete with a hanger in much the same way a blank for a key is now produced. The blanks would then be stored, to await further processing in a Punch Press to form both plain and more intricate patterns by skilled operatives, this processing involved additional die tools that would emboss or remove sections of the blank thus forming the patterns we know today. Anyone with a specific interest in this process may be interested to learn that this is covered in some detail in the society Video/ DVD entitled, Horse Brasses, Origin, History & Collecting.

ssing machines stamped out blanks complete with a hanger in much the same way a blank for a key is now produced. The blanks would then be stored, to await further processing in a Punch Press to form both plain and more intricate patterns by skilled operatives, this processing involved additional die tools that would emboss or remove sections of the blank thus forming the patterns we know today. Anyone with a specific interest in this process may be interested to learn that this is covered in some detail in the society Video/ DVD entitled, Horse Brasses, Origin, History & Collecting.

Other examples were simply pressed and cut at the same time requiring no additional work other than polishing prior to sale. These were fashioned using specially made positive and negative dies. Brass sheet was fed between the falling die tools cutting and pressing out the shape required in one blow ready for sale. An early form of mass production, but with in notable cases, limited numbers produced. Over time these dies were further developed so that stepped cones or floral dome shapes could be included in the production. ( the cone shapes are often refered to as Bee hives) The blanks could now also be embossed prior to the other cutting dies being employed to remove diamond or triangular shaped pieces ( called "Cut outs" ) around the border.

No one is completely sure how the blanks were positioned, so that cutting and perforating the ‘surround’ could be undertaken but there is enough evidence to suggests the operative did most of it ‘by eye’; as a number of so called ‘Friday afternoon brasses‘exist. Rather crude examples indeed.

The average stamped brass is much lighter than a cast brass, both the front and the back face are also smooth except where the action of the punches has raised a small edge or arris round the cut-out or perforation.

As the 19th century drew to a close, a new type of stamped brass appeared. These were frames to house an applied ceramic pot centre, (often made in Staffordshire) held in place by a decorative pin. There are a wide variety of colours available but many had a patriotic red-white-and-blue theme.

These first appeared in the early 1890’s and their production continued until the 1920’s. These ceramic centred brasses are commonly called "pots" by collectors and some were also added to specially made rosettes( ear pieces), used on the heavy horse bridles.

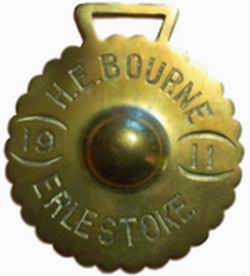

Pots were also used t o enhance other brass decorations; like the two shown below, adding a splash of colour to this Edward VII coronation decoration or to this more personalised Hame plate.

o enhance other brass decorations; like the two shown below, adding a splash of colour to this Edward VII coronation decoration or to this more personalised Hame plate.

In that example I presume the horse’s name was Bob rather than its owner.

In that example I presume the horse’s name was Bob rather than its owner.

"Pots" were often given as Prizes. The Winners and runner-ups of the various Cart horse Parades held through out Great Britain often recieved them.One is led to wonder if Red ones were awarded for Ist Place, Blue for Second and white for third place.

Sometime around the 1950's a poorer quality pot type appeared ( both cast and pressed housings were used )This line introduced additional colours to the range of ceramic centred brasses; yellow, olive green, and plum now appeared.

The development of stamped brasses with a Royal theme is also interesting; the first types concerned Queen Victoria, a cast bust of this monarch was attached to a pressed blank having an embossed diamond surround.  Another was created in much the same manner using one with a diamond surround. At the time of her death in 1901 a brass commemorating her reign, included lettering for the first time.

Another was created in much the same manner using one with a diamond surround. At the time of her death in 1901 a brass commemorating her reign, included lettering for the first time.

Then the following Kings, Edward VII and George V were also given this consideration.

Innovations continued, and specially made brasses now included sepia or coloured photographs of the reigning Monarch; these were covered by celluloid, and inserted into a small-embossed central void.

Another group of brass are those that have been hand engraved, these are farmer or owner brasses, two are shown here below.

Aftermarket or post factory types, are somewhat personalised too by their owners according to taste. Having had pieces added to them when a section or piece is worn away /broken in the case of many "Pot "housings

Yet another group which is often confused with post factory alternations are those that were produced as limited runs. The exact mumbers produced will never been known . However they are of interest being prized by those that have them.Some are marriages (below) between cast and stamped components to form designs of interest.

Tinker brasses

Often d escribed as Gypsy brasses, though the common belief that Gypsies made horse brasses is largely a myth. Nowadays the term Gypsy is commonly confused with Tinkers, 19th Century itinerant metalworkers. Suffice it to

escribed as Gypsy brasses, though the common belief that Gypsies made horse brasses is largely a myth. Nowadays the term Gypsy is commonly confused with Tinkers, 19th Century itinerant metalworkers. Suffice it to say then, this group are those brasses which have been made by hand worked by Tinkers or other skilled artisans as special orders, or to personal taste. They are normally "one offs". Some however, do have pressed features, which may have indicated an individual flair in the factories themselves, and certainly someone with an extensive tool-kit.

say then, this group are those brasses which have been made by hand worked by Tinkers or other skilled artisans as special orders, or to personal taste. They are normally "one offs". Some however, do have pressed features, which may have indicated an individual flair in the factories themselves, and certainly someone with an extensive tool-kit.

The  last group of stamped brasses produced celebrated the Silver Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II in 1977 & her Ruby Jubliee in 1992 these were series of "pot" brasses.

last group of stamped brasses produced celebrated the Silver Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II in 1977 & her Ruby Jubliee in 1992 these were series of "pot" brasses.

Siver Jubliee 1977 Ruby Jubliee 1992

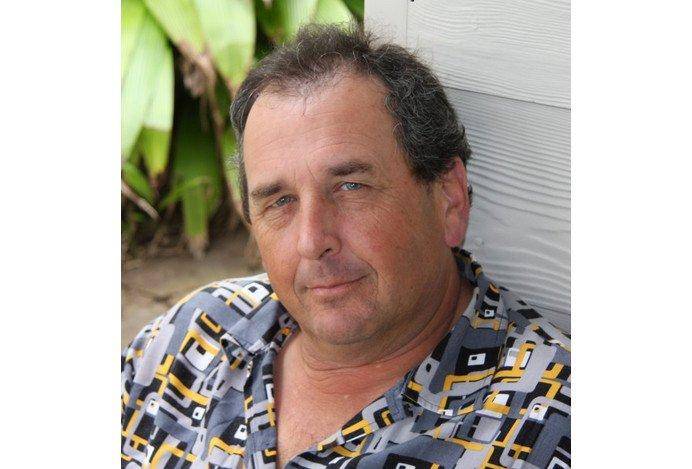

Editorial; In 2007 Maurice A. Hill of Australia printed the private publication, Stampers, which covered stamped brasses in detail for the first time. Maurice wrote that, "There are a wide variety of designs and patterns within this reference, a large number do not appear in any other work concerning harness decorations, certainly not in colour. It is hoped that only a few may have escaped my attention." However, this work was well received amongst collectors and quickly sold out and it was prophesised that, according to Sods Law, as soon as it was published, many more, rare or previously unknown types might come out of the woodwork, which indeed they did. In the light of this Maurice has agreed to re-work his original volume into a format that we hope will be published by the NHBS for its membership, so I am sure you will join me in wishing Maurice, Good Luck, for this keenly awaited publication.

We are very sad to report that Maurice passed away suddenly in 2013, and our most sincere condolences go out to his family.

We are very sad to report that Maurice passed away suddenly in 2013, and our most sincere condolences go out to his family.

He will be sadly missed.